The salad girl | Las ensaladas de la senorita Giselle, 2016

Commentary by Roy C Boland Osegueda, Professor of Spanish at UNSW.

"The Salad Girl" is an elegantly composed and scrupulously structured short story by Esteban Bedoya, a Paraguayan writer currently resident in Canberra, the Australian capital. In due course it will form part of an anthology of "Australian stories" by this Latin American author, whose recent publications convey, with an outsider's keen insight, the idiosyncrasies of a country with which he has become well acquainted and for which he expresses a warm fondness.

According to the great Peruvian writer, Mario Vargas Llosa, there are as many possible readings of a work of fiction as there are readers. One reading of "The Salad Girl" is that of a confessional monologue by an angst-ridden narrator who, lying on a metaphorical couch, recounts a bizarre sexual experience to a reader invited to play the role of therapist. The narrator—or patient—is Carlos Arzamendia, a short, fat, widowed sexagenarian Paraguayan of Guaraní descent. Conscious of his ethnicity, perhaps even embarrassed by it in Anglo-Celtic Australia, Carlos self-deprecatingly refers to himself as an "Indian".

The salad girl e-book is now available on Kindle, click here.

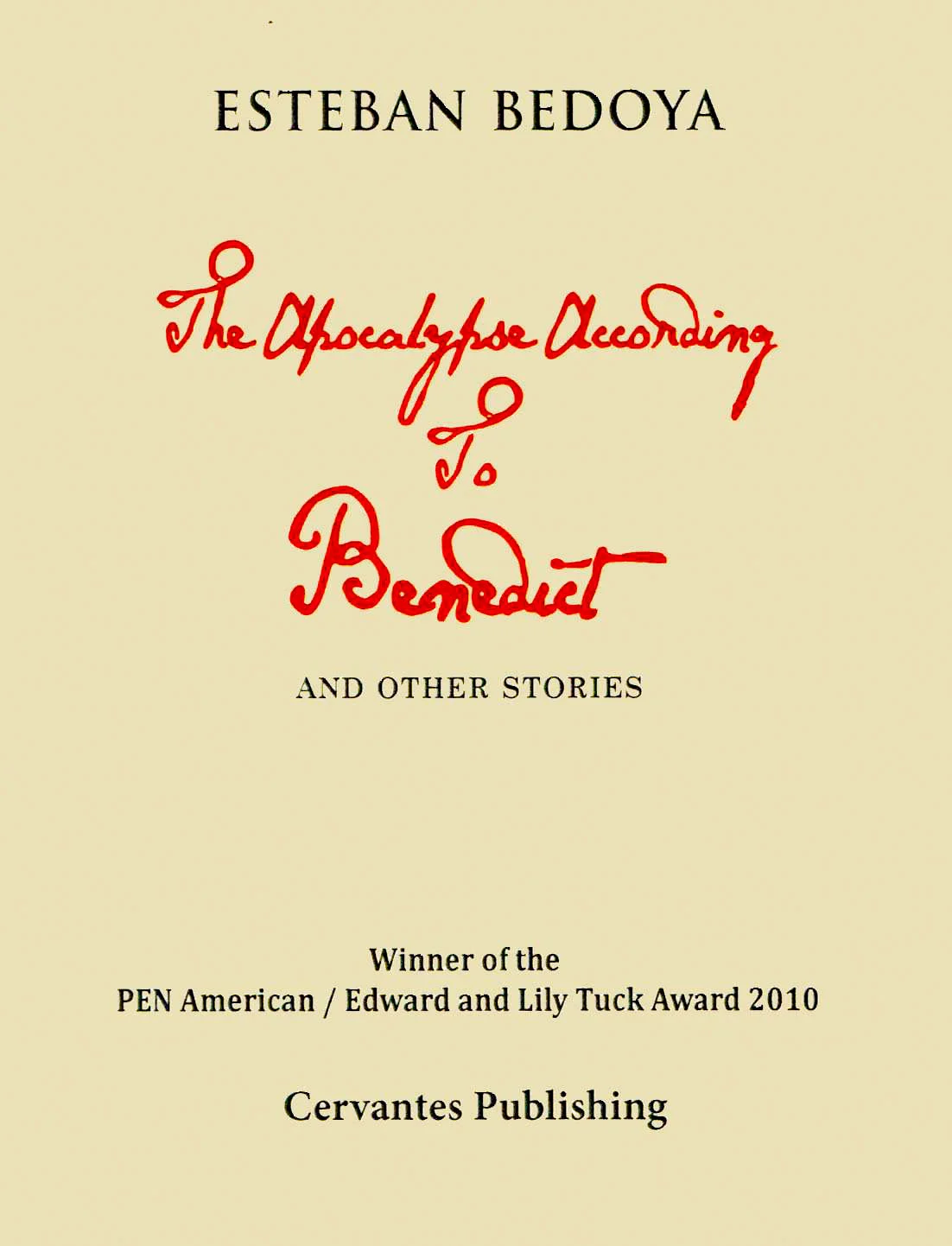

The Apocalypse According to Benedict and other stories, 2012

Winner of the PEN America / Edward and Lucy Tuck Award 2010

A couple of weeks ago I met the Paraguayan ambassador to Australia, Esteban Bedoya, after having read his short novel, The Apocalypse According to Benedict. It seems to be a minor Latin America tradition to have diplomats who are also writers. Octavio Paz was Mexican ambassador to India, while Pablo Neruda was Chile’s ambassador in France. A Canberra dinner party turned into a lively argument about Catholicism – a topic I haven’t really considered since my teens.

One wonders if Bedoya has some secret hot-line into the Vatican. When he published The Apocalypse According to Benedict in 2008 it seemed an audacious fantasy that Pope Benedict XVI, AKA. Joseph Ratzinger, would ever retire from this highest of worldly offices. Popes don’t retire: they assume the Papal throne at an advanced age and moulder away on the job. One need only think of Benedict’s predecessor, Pope John Paul II, who died at the age of 85, suffering from Parkinson’s Disease and severe degenerative arthritis. By the end of his life John Paul II had survived two assassination atempts and several cancer scares, but his decrepitude was alarming.

In his novella Bedoya has Benedict retire – and so it came to pass. On 11 February 2013, two months’ short of his 86th birthday, the Pope announced his intention to step down, citing “a lack of strength of mind and body”.

Having witnessed the lamentable final years of his friend and ally, John Paul II, one can understand Benedict’s actions, even if had been 598 years since the previous Papal resignation. That was when Gregory XII was forced to resign in order to end the Great Schism which divided the Catholic Church from 1378 to 1418.

The novelty of Bedoya’s story is that the Pope does not resign solely because of declining health. His decision follows a landmark decision that throws the Church into crisis. Those who considered the Pontiff to be an ultra-conservative, now call him “Benedict the Revolutionary”.

Having detonated his bomb the Pope declines the offer of spending his retirement in the Vatican and withdraws to his native Bavaria. The real Benedict has remained in Rome, but with the caveat that his only ‘revolutionary’ gesture was the resignation itself.

The startling parallels between art and life lend a seductive power to Bedoya’s imaginative rewiring of reality. Is it impossible that the real Benedict might have felt the same anxieties about the “crisis of faith” faced by the Church today? The crisis is real enough with the Catholic Church often resembling a vast multinational corporation peddling a medieval view of personal morality. Believers around the world find their faith tested by doctrines seemingly at odds with the circumstances of their lives.

Bedoya’s Pope takes decisive action then resigns while the shock waves are still radiating outwards. He knows there can be no stopping the forces he has unleashed. For the reader this extraordinary scenario has a eerie plausibility. One can believe the real Benedict nurtured similar ambitions which never came to fruition. The author leads us into this state of heightened credulity by presenting the Pope as a creature of flesh-and-blood who talks freely about his childhood temptations, feeling the conflict between his vows to the Church and the pangs of sexual desire.

For the Church the Pope is an immaculate figure whose life and actions can only be exemplary. Bedoya’s version seems much more like a mere mortal – more capable of eliciting our sympathies, less demanding of reverence.

And so we read The Apocalypse According to Benedict as both an outlandish work of fiction and a tale that brings a touch of earthy realism into our views of that otherworldly kingdom, the Vatican. The book dispells the air of professional mystery concocted by the Church and leads us to focus on those greater mysteries contained within the human heart.

Click here to view The Apocalypse according to Benedict and other stories on Kindle.